CAPITVLVM TRICESIMVM QVARTVMTHIRTY-FOURTH CHAPTER

DE ARTE POETICAON POETIC ART

I

Epistula Aemilii convivis recitata, “Ergo” inquit Aemilia “non modo filio, sed etiam fratri meo bracchium vulneratum est.”

Fabia: “Quisnam vulneravit filium tuum?”

Aemilia: “Medicus bracchium eius scalpello suo acuto secuit! Qui, cum Quintus heri de alta arbore cecidisset, pedem eius turgidum vix tetigit, sed misello puero sanguinem misit! Profecto filius meus non opera medici sanabitur, sed diis iuvantibus spero eum brevi sanum fore. Liberine tui bona valetudine utuntur?”

Fabia: “Sextus quidem hodie naso turgido atque cruento e ludo rediit, cum certavisset cum quibusdam pueris qui eum laeserant.”

Aemilia: “Cum pueri ludunt, haud multum interest inter ludum et certamen. Marcus vero, si quis eum laedere vult, ipse se defendere potest.”

Fabia: “Item Sextus scit se defendere, dummodo cum singulis certet. Nemo solus eum vincere potest. Sed filius meus studiosior est legendi quam pugnandi.”

Aemilia: “Id de Marco dici non potest. Is non tam litteris studet quam ludis et certaminibus!”

Hic Cornelius mulieres interpellat: “Ego quoque ludis et certaminibus studeo, dummodo alios certantes spectum! Modo in amphitheatro certamen magnificum spectavi: plus trecenti gladiatores certabant. Plerique gladiis et scutis armati erant, alii retia gerebant.”

Aemilia, quae certamen gladiatorium non spectavit, a Cornelio quaerit 'quomodo gladiatores retibus certant?'

Cornelius: “Alter alterum in rete implicare conatur, nam qui reti implicitus est non potest se defendere et sine mora interficitur, nisi tam fortiter pugnavit ut spectatores eum vivere velint. Sed plerumque is qui victus est occiditur, victor vero palmam accipit, dum spectatores delectati clamant ac manibus plaudunt.”

Iulius: “Mihi non libet spectare ludos istos feroces. Malo cursus equorum spectare in circo.”

Cornelius: “Ludi circenses me non minus iuvant quam gladiatori: modo in amphitheatrum, modo in circum eo. Sed ex novissimis circensibus maestus abii, cum ille auriga cui plerique spectatores favebant ex curru lapsus equis procurrentibus occisus esset. Illo occiso spectatores plaudere desierunt ac lugere coeperunt.”

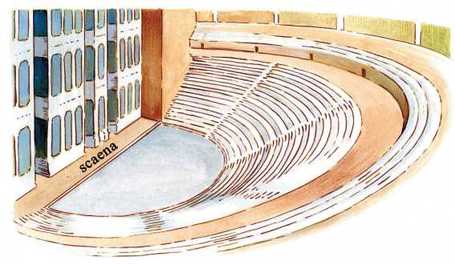

Fabia: “Ego ludos scaenicos praefero: malo fabulas spectare in theatro. Nuper spectavi comoediam Plauti de Amphitryone, duce Graecorum, cuius uxor Alcmena ab ipso Iove amabatur. Dum dux ille acer et fortis procul a domo bellum gerit, Iuppiter se in formam eius mutavit, ut Alcmenam viseret; quae, cum putaret coniugem suum esse, eum in cubiculum recepit...”

Cornelius: “...et decimo post mense filios geminos peperit, quorum alter fuit Hercules. Illa fabula omnibus nota est. Sed scitisne cur feminis libeat in theatrum ire? Ovidius poeta, qui ingenium mulierum tam bene noverat quam ipsae mulieres, rationem reddit hoc versu:

Spectatum veniunt, veniunt spectentur ut ipsae!”

Fabia: “Et viri veniunt ut bellas feminas spectent!”

Having recited Aemelius's letter, Emilia says, "Therefore not only my son but even my brother's arm is wounded."

Fabia: "Who wounded your son?"

Emilia: "The doctor cut his arm with his sharp scalpel! He who, when Quintus fell from a tall tree yesterday, barely touched his foot, but drained blood from the miserable boy! Of course my son will not be healed by the doctor's work, but with the help of the gods, I hope he will be well soon. Are your sons enjoying good health?"

Fabia: "Sextus indeed returned from school today with a swollen and bloody nose, when he had fought with some boys who injured him."

Emilia: "When boys play there is not much difference between play and fighitng. But Marcus, if someone wants to hurt him, can defend himself."

Fabia: "Likewise Sextus knows to defend himself, if only he fights with one. No one alone can overcome him. But my son is more eager for reading than fighting."

Emilia: "That cannot be said of Marcus. He is not so eager for letters as playing and fighting!"

Here Cornelius interrupts the women: "I am also eager for playing and fighting, if only I am wacthing others fight! I watched such a magnificent fight in the ampitheatre: more than three hundred gladiators were fighting. Nearly all were armed with swords and shields, others bore nets."

Emilia, who has not watched the gladiator's fight, asks Cornelius 'how gladiators fight with nets?'

Cornelius: "One tries to entangle the other in a net, for he who is entangled in a net cannot defend himself and is killed without delay, unless he fought so bravely that the spectators wish him to live. But nearly always he who is vanquished is killed, and the winner receives a palm, while the delighted spectators shout and clap their hands."

Julius: "It is not pleasing to me to watch such fierce games. I prefer to watch the horse race in the circus."

Cornelius: "The circus games do not delight me less than the gladiators: now I go to the ampitheater, then I go to the circus. But I left the most recent circus sad, when the charioteer who almost all the spectators favored fell from his chariot and was killed by the rushing horses. At his death the spectators stopped clapping and began mourning."

Fabia: "I prefer theatrical plays: I prefer to see stories in the theater. Recently I watched the comedy of Plautus of Amphitryon, leader of the Greeks, whose wife Alcmena was loved by Jove himself. While that keen and brave leader was away from home fighting a war, Jupiter changed his form to see Alcmena, who when she thought him to be her husband, received him in her room..."

Cornelius: "... and ten months later gave birth to twin sons, one of which was Hercules. Everyone knows that tale. But do you know why it pleases women to go to the theater? The poet Ovid, who knew the nature of women as well as women themselves, gives the reason in this verse:

They come to see, they come to be seen themselves!"

Fabia: "And men come to see the beautiful women!"

II

Tum Iulius, qui artis poeticae studiosus est, “Ovidius ipse” inquit “id dicit. Ecce principium carminis quod scripsit ad amicam secum in circo sedentem:

Non ego nobilium sedeo studiosus equorum;

cui tamen ipsa faves vincat ut ille precor.

Ut loquerer tecum veni tecumque sederem,

ne tibi non notus quem facis esset amor.

Tu cursus spectas, ego te - spectemus uterque

quod iuvat, atque oculos pascat uterque suos!”

Cornelius: “Ego memoria tenero versus Ovidii de puella quae poetam industrium prohibebat bellum Troianum canere et fatum regis Priami:

Saepe meae “Tandem” dixi “discede!” puellae

- in gremio sedit protinus illa meo.

Saepe “Pudet!” dixi. Lacrimis vix illa retentis

“Me miseram! Iam te” dixit “amare pudet?”

Implicuitque suos circum mea colla lacertos

et, quae me perdunt, oscula mille dedit!

Vincor, et ingenium sumptis revocatur ab armis,

resque domi gestas et mea bella cano.”

Fabia: “Iste poeta viris solis placet. Me vero magis iuvant carmina bella quae Catullus scripsit ad Lesbiam amicam. Si tibi libet, Iuli, recita nobis e libro Catulli.”

“Libenter faciam” inquit Iulius, “sed iam nimis obscurum est hoc triclinium; in tenebris legere non possum. Lucernas accendite, servi!”

Lucernis accensis, Iulius librum Catulli proferri iubet, tum “Incipiam” inquit “a carmine de morte passeris quem Lesbia in deliciis habuerat:

Lugete, o Veneres Cupidinesque,

et quantum est hominum venustiorum:

passer mortuus est meae puellae,

passer, deliciae meae puellae,

quem plus illa oculis suis amabat;

nam mellitus erat suamque norat

ipsam tam bene quam puella matrem,

nec sese a gremio illius movebat,

sed circumsiliens modo huc modo illuc

ad solam dominam usque pipiabat.

Qui nunc it per iter tenebricosum

illuc, unde negant redire quemquam.

At vobis male sit, malae tenebrae

Orci, quae omnia bella devoratis:

tam bellum mihi passerem abstulistis.

O factum male! O miselle passer!

tua nunc opera meae puellae

flendo turgiduli rubent ocelli!

“His versibus ultimis poeta veram rationem doloris sui reddit: quod oculi Lesbiae lacrimis turgidi erant ac rubentes! Tunc enim Catullus Lesbiam solam amabat atque amorem suum perpetuum fore credebat. Ecce aliud carmen quo mens poetae amore accensa demonstratur:

Vivamus, mea Lesbia, atque amemus,

rumoresque senum severiorum

omnes unius aestimemus assis!

Soles occidere et redire possunt -

nobis, cum semel occidit brevis lux,

nox est perpetua una dormienda.

Da mi basia mille, deinde centum,

dein mille altera, dein secunda centum,

deinde usque altera mille, deinde centum!

Dein, cum milia multa fecerimus,

conturbabimus illa, ne sciamus,

aut ne quis malus invidere possit,

cum tantum sciat esse basiorum.

“Catullus Lesbiam uxorem ducere cupiebat, nec vero illa Catullo nupsit, etsi affirmabat 'se nulli alii viro nubere malle.' Mox vero poeta de verbis eius dubitare coepit:

Nulli se dicit mulier mea 'nubere malle

quam mihi, non si se Iuppiter ipse petat!'

Dicit. Sed mulier cupido quod dicit amanti,

in vento et rapida scribere oportet aqua!

“Postremo poeta intellexit Lesbiam infidam et amore suo indignam esse, neque tamen desiit eam amare. Ecce duo versus qui mentem poetae dolentem ac dubiam inter amorem et odium demonstrant:

Odi et amo. quare id faciam, fortasse requiris?

Nescio, sed fieri sentio et excrucior!”

His versibus recitatis convivae diu plaudunt.

Tum Paula “Iam satis” inquit “audivimus de amando et de dolendo. Ego ridere malo, neque iste poeta risum excitat. Quin versus iocosos recitas nobis?”

Cui Iulius “At Catullus” inquit “non tantum carmina seria, sed etiam iocosa scripsit. Ecce versus quibus poeta pauper quendam amicum divitem, nomine Fabullum, ad cenam vocavit:

Cenabis bene, mi Fabulle, apud me

paucis, si tibi di favent, diebus,

-

si tecum attuleris bonam atque magnam

cenam, non sine candida puella

et vino et sale et omnibus cachinnis.

Haec si, inquam, attuleris, venuste noster,

cenabis bene - nam tui Catulli

plenus sacculus est aranearum.”

Then Julius, who studied the poetic arts, says, "Ovid himself says this. Here is the beginning of the poem that he wrote to his girlfriend sitting with him in the circus:

I am not sitting here interested in the famous horses;

nevertheless to the one you favor I pray that one will win.

I came to speak with you and sit with you,

Lest

you do not know the love that you have made

You watch the race, I you - Let each of us watch

What pleases, and each of us feed their own eyes!"

Cornelius: "I remember Ovid's verse about the girl who prevented the industrious poet from singing about the Trojan war and fate of King Priam:

Often I said to my girl 'Leave at last!'

- immediately she sits in my lap.

Often I said 'Shame!' She can barely hold back tears

'Poor me!' she said, 'now are you ashamed to be in love?'

She wrapped her arm around my neck

and, destroys me, gave me a thousand kisses!

I am defeated, and my character is

recalled from the weapons,

and I sing of things done at home and my beauty."

Fabia: "That poet is only pleasing to men. But I am pleased more but the beautiful poem that Catallus wrote to his girlfriend Lesbia. If it pleases you Julius, recite to us from the book of Catullus."

"I will gladly do it," says Julius, "but now this dining room is too dark; I cannot read in the dark. Increase the light servants!"

With the light increased, Julius commands that Catullus's book be brought to him, then he says, "I will begin with the poem about the death of the sparrow that Lesbia loved:

Mourn, o Venus's and Cupids,

and how many beautiful men there are:

my girl's sparrow is dead,

sparrow, the girl's delight,

That she loved more than her own eyes;

for he was sweeter

than honey and he knew her

as well as the girl knew her mother,

nor did it move itself from her lap,

but jumping around now here now there

but chirped to his mistress alone.

Who is now going on a journey through the darkness

from where they deny anyone to return.

But it may be bad for you, evil darkness

of Orcus, who devours everything beautiful:

you have taken such a beautiful sparrow from me.

O evil deed! O miserable sparrow!

now for your work my girl's

swollen eyes are red from crying!

"In these last words the poet gives the true reason for his sorrow: because Lesbia's eyes were swollen with tears and red! For then Catullus loved Lesbia alone and believed his loved would last forever. Here is another poem in which the mind of the poet is shown to be inflmaed with love:

Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love,

and the rumors of stern old men

let us value all as one penny!

Suns sun and can rise again -

for us,

when the brief light has set

an eternal night must be slept.

Give me a thousand kisses, then a hundred,

then another thousand, then a second

hundred,

then yet another thousand, then a hundred!

Then, when we have made many thousands,

we will confound those, that we may not know,

nor can one who is evil envy us,

when such a great number of kisses is not known.

"Catullus was eager to marry Lesbia, but she did not marry Catullus, although she affirmed that she would not marry any other man. But soon the poet began to doubt her words:

My woman says that she prefers to be marry no one

more than me, not even if Jupiter himself seeks her!

She says.

But what a woman says to a lover,

is fitting to be write on the wind and the rapid water!

"Finally the poet knew Lesbia to be unfaithful and not worthy of his love, but nevertheless did not stop loving her. Here are two verses that show the poet's sorrowful mind and doubt between love and hate:

I hate and love, why would I do that, you might ask?

I don't know, but I feel it happening and I am tortured!"

With these verses recited the dinner guests clap for while.

Then Paula says, "Enough already. We have heard of love and of sorry. I prefer to laugh, but that poet does not arouse laughter. Why don't you recite funny lines to us?"

Which Julius says, "But Catullus wrote not only serious poems, but even funny ones. Here are the verses in which the poor poet invited a rich friend, named Fabullus, to dinner:

You will dine well, my Fabullus, with me

in a few days, if the gods favor you,

- if you bring with you a good and great

dinner, not without a fair skinned girl

and wine, salt, and all

the laughter.

If you bring these, our friend,

you will dine well - for the bag of your

Cattulus is full of cobwebs."

III

Hi versus magnum risum movent. Tum vero Cornelius “Bene quidem” inquit “et iocose scripsit Catullus, nec tamen versus eius comparandi sunt cum epigrammatis sale plenis quae Martialis in inimicos scripsit. Semper libros Martialis mecum in sinu fero.”

Ab omnibus rogatus ut epigrammata recitet, Cornelius libellum evolvit et “Incipiam” inquit “a versibus quos poeta de suis libellis scripsit:

Laudat, amat, cantat nostros mea Roma libellos,

meque sinus omnes, me manus omnis habet.

Ecce rubet quidam, pallet, stupet, oscitat, odit.

Hoc volo: nunc nobis carmina nostra placent.”

Post hoc principium Cornelius aliquot epigrammata Martialis recitat, in iis haec quae scripta sunt in alios poetas:

Cur non mitto meos tibi, Pontiliane, libellos?

Ne mihi tu mittas, Pontiliane, tuos. -

Versiculos in me narratur scribere Cinna.

Non scribit, cuius carmina nemo legit. -

Nil recitas et vis, Mamerce, poeta videri.

Quidquid vis esto, dummodo nil recites!

Ecce alia epigrammata Martialis quae Cornelius convivis attentis atque delectatis recitat:

Non amo te, Sabidi, nec possum dicere quare.

Hoc tantum possum dicere: non amo te! -

Nil mihi das vivus, dicis 'post fata daturum.'

Si non es stultus, scis, Maro, quid cupiam! -

'Esse nihil' dicis quidquid petis, improbe Cinna.

Si nil, Cinna, petis, nil tibi, Cinna, nego! -

Nescio tam multis quid scribas, Fauste, puellis.

Hoc scio, quod scribit nulla puella tibi!

Sequuntur epigrammata quibus deridentur feminae, praecipue anus, ut Laecania et Paula:

Thais habet nigros, niveos Laecania dentes.

Quae ratio est? Emptos haec habet, illa suos! -

Nubere vis Prisco: non miror, Paula: sapisti.

Ducere te non vult Priscus: et ille sapit! -

Nubere Paula cupit nobis, ego ducere Paulam

nolo: anus est; vellem, si magis esset anus!

Ceteris ridentibus “Quid ridentis?” inquit Paula, “Num haec in me, uxorem formosam atque puellam, scripta esse putatis?”

Cornelius: “Minime, Paula. Nec scilicet in te, sed in Bassam scriptum est hoc:

Dicis formosam, dicis te, Bassa, 'puellam'.

Istud quae non est dicere, Bassa, solet!”

Hoc audiens erubescit Paula atque ceteri convivae risum vix tenent. Cornelius vero prudenter “Non omnia” inquit “iocosa sunt carmina Martialis. Ecce duo versus de fato viri pauperis, et quattuor in Gelliam, quae coram testibus lacrimas effundit super patrem mortuum:

Semper pauper eris, si pauper es, Aemiliane.

Dantur opes nullis nunc nisi divitibus. -

Amissum non flet cum sola est Gellia patrem;

si quis adest, iussae prosiliunt lacrimae!

Non luget quisquis laudari, Gellia, quaerit:

ille dolet vere, qui sine teste dolet.”

Centum fere epigrammatis recitatis, Cornelius cum hoc finem facit recitandi:

Cui legisse satis non est epigrammata centum,

nil illi satis est, Caedicione, mali!

Rident omnes et Cornelio valde et diu plaudunt.

These verses stir a great laughter. But then Cornelius says, Well indeed and Catullus wrote humorously, and yet nevertheless his verses cannot be compared with the salt filled epigrams of Matial against his enemies. I always carry Martia's books with me."

Asked by everyone to recite an epigram, Cornelius opens a book and says, "I will begin from verses which the poet wrote about his own books:

My Rome praises, loves, sings my books,

all pockets have me, every hand.

See them blush, turn pale, shocked, yawn, hate.

I want this: now

my poems please me."

After beginning this Cornelius recites antoher epigram of Martial, in which wrote these things against other poets:

Why don't I send you my little books Pontilianus?

Lest you send me yours Pontilianus. -

It is said that Cinna writes little verses about me.

He will not be a writer, whose poems no one reads. -

You recite nothing and you want to be seen as a poet Mamerce

Be whatever you want, but only if recite nothing!

Here are other epigrams of Martila that Cornelius recites to the attentive and delighted guests:

I do not love you Sabidus, but I can't say why.

I can only says this: I do not love you! -

You don't give me anyhting alive, you say 'it will be given after fate.'

If you are not a fool Maro, you know what I desire! -

You say 'it is nothing' whatever you ask, wicked Cinna.

If you ask for nothing Cinna, nothing will I deny to you! -

I don't what you write to so many girls Faustus.

I know this, no girl will write to you!

The following epigrams mock women, especially old women, like Laecania and Paula:

Thais has black teeth, Laecania snowy white.

What is the reason? One has those she bought, the other her own! -

You wish to marry Prisco: I do not wonder Paula, you are wise.

Priscus does not wish to marry you, he too is wise! -

Paula wishes to marry me, I do not wish to marry Paula

She is an old woman. I might wish it if she had been an older woman!

With the others laughing, Paula says, "Why are you laughing? You don't think these things to be written about me, a beautiful wife and girl do you?"

Cornelius: "Certainly not Paula. Nor was this written against you but Bassa:"

You say that you are beautiful girl Bassa.

The one who is not is accustomed to say that Bass!"

Hearing this Paula blushes and the other guests can barely hold back their laughter. But Cornelius wisely says, "Not all of Martial's poems are humorous. Here are two verses concerning the fate of poor men, and four against Gellia, who poured out tears over her dead father in the presence of witnesses:

You will always be poor if you are poor Aemiliane.

Wealth is given to none now besides the rich. -

Gellia does not weap alone for her dead father;

if someone is present, tears

spring forth at her comman!

He does not mourn who seeks praise Gellia:

he truly sorrows, who sorrows without a witness."

Having recited about a hundred epigrams, Cornelius ends his recitation with this:

He who is not satisfied with the reading of a hundred epigrams,

Caecilianus, is not satisifed with any amount of evil!

They all laugh and applaud Cornelius loudly and for a long time.

GRAMMATICA LATINA

De versibus

[I] Syllabae breves et longae

Non ego nobilium sedeo studiosus equorum.

Hic versus constat ex his syllabis: no-ne-go- no-bi-li-um- se-de-o- stu-di-o-su-s e-quo-rum.

Syllaba brevis est quae in vocalem brevem (a, e, i, o, u, y) desinit; quae desinit in vocalem longam (ā, ē, ī, ō, ū, ȳ) aut in diphthongum (ae, oe, au, eu, ei, ui) aut in consonantem (b, c, d, f, g, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, x) syllaba longa est.

Syllabae breves: ne, go, bi, li, se, de, stu, di, su, se; syllabae longae: no, um, o, quo, rum.

Haec nota [ ˘ ] syllabam brevem significat, haec [ ] syllabam longam: non ego nobilium sedeo...

Consonantes br, gr, cr, tr, quae initium syllabae facere solent (ut li-bri), interdum dividuntur: nig-ros, pat-rem.

Vocalis -o ultima interdum fit brevis: vo-lo, ne-mo.

[II] Syllabae coniunctae.

Litterae vocabulorum ultimae cum vocalibus sequentibus coniunguntur his modis:

[A] Consonans ultima cum vocali prima (vel h-) vocabuli sequentis ita coniungitur ut initium syllabae faciat: a-nu-s est; vin-ca-t u-t il-le.

[B] Vocalis ultima (item -am, -em, -um, -im) ante vocalem primam (vel h-) vocabuli sequentis eliditur:

Vivamus, mea Lesbia, atque amemus: Lesbi'atqu'amemus

Odi et amo. Quare id faciam: Od'et . .. Quar'id ...

In est et es eliditur e: sola est: sola'st, verum est: verum'st, bella es: bella's.

[III] Pedes

Singuli versus dividuntur in pedes, qui binas aut ternas syllabas continent. Pedes frequentissimi sunt trochaei, iambi, dactyli, spondei. Trochaeus constat ex syllaba longa et brevi, ut lu-na, iambus ex brevi et longa, ut vi-ri, dactylus ex longa et duabus brevibus, ut fe-mi-na, spondeus ex duabus ongis, ut ne-mo.

[IV] Versus hexameter

Non-ego| nobili|um sede|o studi|osus e|quorum

Hie versus hexameter vocatur a numero pedum, nam sex Graece dicitur hex. Hexameter constat ex quinque pedibus dactylis et uno spondeo (vel trochaeo); pro dactylis saepe spondei inveniuntur, sed pes quintus semper dactylus est:

LATIN GRAMMAR

VOCABVLA

scalpellum, scalpelli n.

opera, operae f.

ludus, ludi m.

certamen, ceramenis n.

gladiator, gladiatoris m.

rete, retis n.

spectator, spectatoris m.

palma, palmae f.

circus, circi m.

auriga, aurigae m.

theatrum, theatri n.

comoedia, comoediae f.

ingenium, ingenii n.

ratio, rationis f.

principium, principii n.

fatum, fati n.

gremium, gremii n.

tenebrae, tenebrarum f.

lucerna, lucernae f.

passer, passeris m.

deliciae, delicarum f.

ocellus, occeli m.

mens, mentis f.

basium, basii n.

odium, odii n.

risus, risus m.

cachinnus, cachinni m.

aranea, araneae f.

epigramma, epigrammatis n.

sinus, sinus m.

versiculus, versiculi m.

anus, anus f.

testis, testis m.

opes, opum f.

diphthongus, diphthongi f.

nota, notae f.

turgidus, a, um

misellus, a, um

gladiatorius, a, um

circensis, circense

scaenicus, a, um

acer, acris, acre

geminus, a, um

bellus, a, um

poeticus, a, um

venustus, a, um

mellitus, a, um

tenebricosus, a, um

ultimus, a, um

perpetuus, a, um

dubius, a, um

iocosus, a, um

serius, a, um

niveus, a, um

certo, certare, certavi, certatum

laedo, laedere, laesi, laesum

implico, -are, -avi, implicatus

plaudo, plaudere, plausi, plausum

libere

faveo, favere, favi, fautum

lugeo, lugere, luxi, luctum

accendo, -dere, accendi,

circumsilio, circumsilire, -, -

pipio, pipiare, pipiavi, pipiatum

devoro, -are, -avi, devoratum

conturbo, -are, -avi, conturbatum

nubo, nubere, nupsi, nuptum

affirmo, -are, -avi, affirmatum

requiro, -quirere, -quisivi,

excrucio, -are, -avi, excruciatum

oscito, oscitare, -, -

sapio, sapere, sapivi, -

erubesco, erubescere, erubui, -

prosilio, prosilire, prosilui, -

elido, elidere, elisi, elisum

libenter

plerumque

interdum

dummodo

dein

nil

trochaeus, trochaei m.

iambus, iambi m.

dactylus, dactyli m.

spondeus, spondei m.

hexameter, hexametri m.

pentameter, pentametri m.

hendecasyllabus, a, um

VOCABULARY

small surgical knife

work, care, aid

play, entertainment

combat, battle

gladiator

net, snare

spectator

palm branch, first place

race course, circle, orbit

charioteer, driver

theater

comedy

nature, innate talent

reasoning, account

beginning

fate, destiny

lap, bosom

darkness

oil lamp, midnight oil

sparrow

fun, delight, darling

(little) eye, darling

intellect, mind, reason

kiss

hatred, dislike

laughter

loud laugh, guffaw

spiderʼs web, spider

short poem, inscription

bend, fold, curve

verse

old woman, old maid

witness

resources, wealth

diphthong

writing, mark, letter

swollen, distended

poor, wretched

gladiatorial

circusʼ, used at circus

theatrical

sharp, bitter, keen

twin, double, twin-born

beautiful, pretty

poetic

attractive, charming

honey-sweet

dark

farthest, latest

perpetual, everlasting

uncertain, doubtful

humorous, funny

serious, grave

snowy, white

to fight, to contest

to strike, to hurt

to involve, interweave

to clap, to applaud

freely, frankly

favor (w/DAT), support

to mourn, grieve (over)

to light, to arouse

to leap around

to chirp, to pipe

to devour, consume

to confuse, to disquiet

to marry, be married to

to affirm, to confirm

to require, to seek

to torture, to torment

to gape, to yawn

understand, have sense

to blush at, to redden

jump forward, rush to

to strike out, to expel

with pleasure, willingly

generally, frequently

sometimes

provided (that)

next, in next place

nothing, no concern

trochee, a metrical foot

iambus, iambic trimeter

dactyl

spondee

verse in hexameter

five metric feet

verses of 11 syllables